Inside the beak would be filled with perfumes and herbs to deflect miasma, the horrific stench of 'bad air' from both plague victims and the dead.

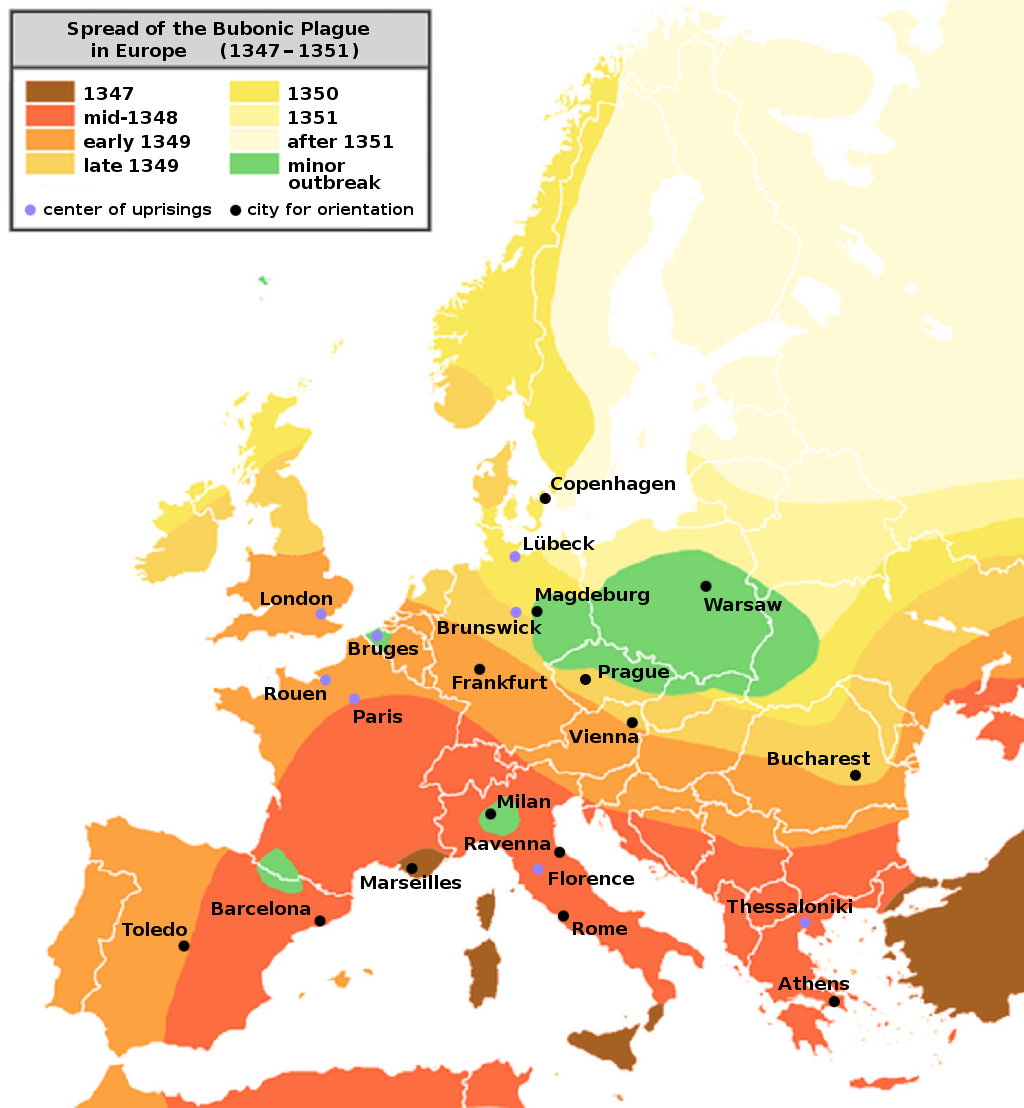

Poland Was Not Actually Spared

Before we go any further we need to clear up a perpetuated myth.

notably the areas of minor outbreaks in Green.

The largest of these areas are centred around historic Poland.

Quarantine of the Polish Borders

One key reason often attributed to the low rates of contagion was the decision by Polish king, Casimir the Great, to close the country's 'borders' shortly after the initial reports from the west and set up internal quarantines.Furthermore, travel time also plays an important factor here. For example, it would normally take 8 days to travel from Prague to Kraków on horseback, even slower if you were on foot. Compare that with the amount of time it would take for the plague to kick-in - between 24 to 72 hours to get sick. So, by the time you reached Kraków or any other city for that matter, you were clearly not going to be let into the city walls!

Poland's Jewish Population

As the historic scapegoats of Europe, the minority Jewish population of Europe suffered at the hands of a bigoted Christian-majority. Once again, thanks to the rulership of Casimir the Great, Jews were offered a safe haven in Paradisus Iudaeorum (ENG: Paradise of the Jews) as Poland became known. This population would thrive for centuries until the atrocities committed in WWII. Unfortunately, when the bubonic plague first hit Europe in October 1347, the gentile population was cynical of the lower rates of infection amongst local Jewry, and therefore subscribed to the idea that the plague was a Jewish conspiracy!American Jewish historian Berel Wein and many others attribute the lower death-rates of Jews during the plague to the adherence of sanitary practices in Jewish law. Simple but regular actions, like washing his or her hands many times throughout the day or that one must not eat food without washing one’s hands, leaving the bathroom and after any sort of intimate human contact are considered basic hygiene in the 21st-century. However, these strict Jewish practices were hardly standard for the majority of common-folk who could go half his or her life without ever washing their hands!

Jewish law also prescribes certain sanitary conditions related to burial of the dead, which were undertaken by the burial sociery, Chevrah Kadisha, who are kind of like funerary directors in Jewish communities. Practices, such as washing the body of the deceased and stationing shomrim, watchers of corpses, ensured that vermin were kept away from the dead. These factors, no doubt, hugely reduced the spread of infection in their communities.

Scenes like this were commonplace all over Europe in the 14th Century, albeit on a much smaller scale in the Kingdom of Poland.

Geography and Climate

As a final pointer that is often discussed as an asset to slowing the spread of disease is Poland's geographical and climatic position in Europe. Firstly, as was touched on before, Poland was more sparsely-populated than elsewhere in Europe and, more-specifically, could hardly compare to the densley-populated Mediterranean coast that had evolved through trade and generally warmer weather. And on the point of weather, Poland's temperate seasonal climate is believed to have mitigated the spread of the plague due to the fact that it was colder than Southern and Western Europe. Taking it a step further, historian Norman F Cantor theorises in his book In the Wake of the Plague: The Black Death and the World It Made: The absence of plague in Bohemia and Poland is commonly explained by the rats' avoidance of these areas due to the unavailability of food the rodents found palatable. Maybe both points are true? Maybe neither? Sadly, we will never know for sure.The Black Death VS Coronavirus

On a virological level, it's impossible to compare the two. The Bubonic Plague is a flea-borne bacterial disease, carried by rodents that jumped to humans. Coronavirus (COVID-19) is a strain of severe acute respiratory syndrome transmitted primarily via respiratory droplets. Whilst the deathtoll of the latter is currently just under 8,000 worldwide, nevertheless shocking, it must be remembered that the Bubonic Plague wiped out 30-60% of medieval Europe and an estimated overall death toll of 75-200 million people in Eurasia. The Black Death truly earnt its name.

a Jew poisoning the well of a Christian settlement.

You like Death? You wanna see more?

As the impact of the bubonic plague was not felt as much in Poland, key sites are non-existent. In our article, Creepy Poland, we talk about a number of sites where bones have been used to furnish the interiors of churches and tombs (how lovely!). Most notably, Kaplica Czaszek (ENG: the Chapel of Skulls) on the Polish/Czech border is furnished with plague victims from the 17th Century - not the same period as the Black Death!Plague crosses, distinguished by their double-beams (this style is known as karawaki in Polish), are commonly-found on roadsides and in regional areas in eastern Poland. In the middle-ages, these were used to mark infected buildings areas of high contagion. Those that are seen around the country now were placed in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, supposedly in response to cholera outbreaks. These evolved into a sort of 'amulet' that the common-folk viewed against many misfortunes: diseases, accidents, curses, theft, storms, lightning and insomnia to name a few! During an October 2020 appeal for strict social-distancing and sanitary standards in churches to prevent the spread of COVID-19, Bishop Piotr Libera of Płock suggested 'placing plague crosses, where it would be possible to pray to the Savior of the world for mercy and salvation'.

Read more on the latest on Coronavirus in Warsaw.

Read more on the latest on Coronavirus in Kraków.

Read more on the latest on Coronavirus in Łódż.

Read more on the latest on Coronavirus in Gdańsk, Sopot and Gdynia.

Read more on the latest on Coronavirus in Katowice.

Read more on the latest on Coronavirus in Wrocław.

Read more on the latest on Coronavirus in Poznań.

Comments