If you think you aren’t familiar with this story, you probably are. It was here that many of the real-life events Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster film Schindler’s List took place. While Schindler’s Factory opened to the public as a museum in 2010, the site of the former Płaszów concentration camp has remained largely in the same state it was left by the Nazis when they abandoned it over 75 years ago.

In the absence of any gallery space or artefacts, Płaszów is not a museum (not yet, anyway - plans have been made to create one). In contrast to Auschwitz, there are no professional tour guides here, no headsets, no multimedia displays, no instructions or design for how to experience the space (except those in this guide). In that sense Płaszów is more of a pilgrimage than a destination, and offers to those who walk its obscure paths the opportunity to engage the past without any pressure or pretence. This is a place where the lives of thousands of people came to an end; a mass cemetery of unmarked graves; the most horrific place in Kraków; and also the most peaceful.

History

Before World War II, Kraków was home to some 65,000 Jews, who once under Nazi occupation (beginning in September 1939) faced almost immediate persecution. Forced ‘resettlement’ (largely to labour camps in the east) began in late 1940 and by the time of the establishment of the Kraków Ghetto in March 1941, the Jewish population had been reduced to some 16,000 individuals crammed into a 20 hectare (50 acre) space in Podgórze. In early 1942 the Nazis began to initiate Hitler’s ‘Final Solution,’ ramping up terror in the Kraków Ghetto with increased round-ups, deportations and street executions that resulted in the gradual reduction of the size and population of the ghetto.

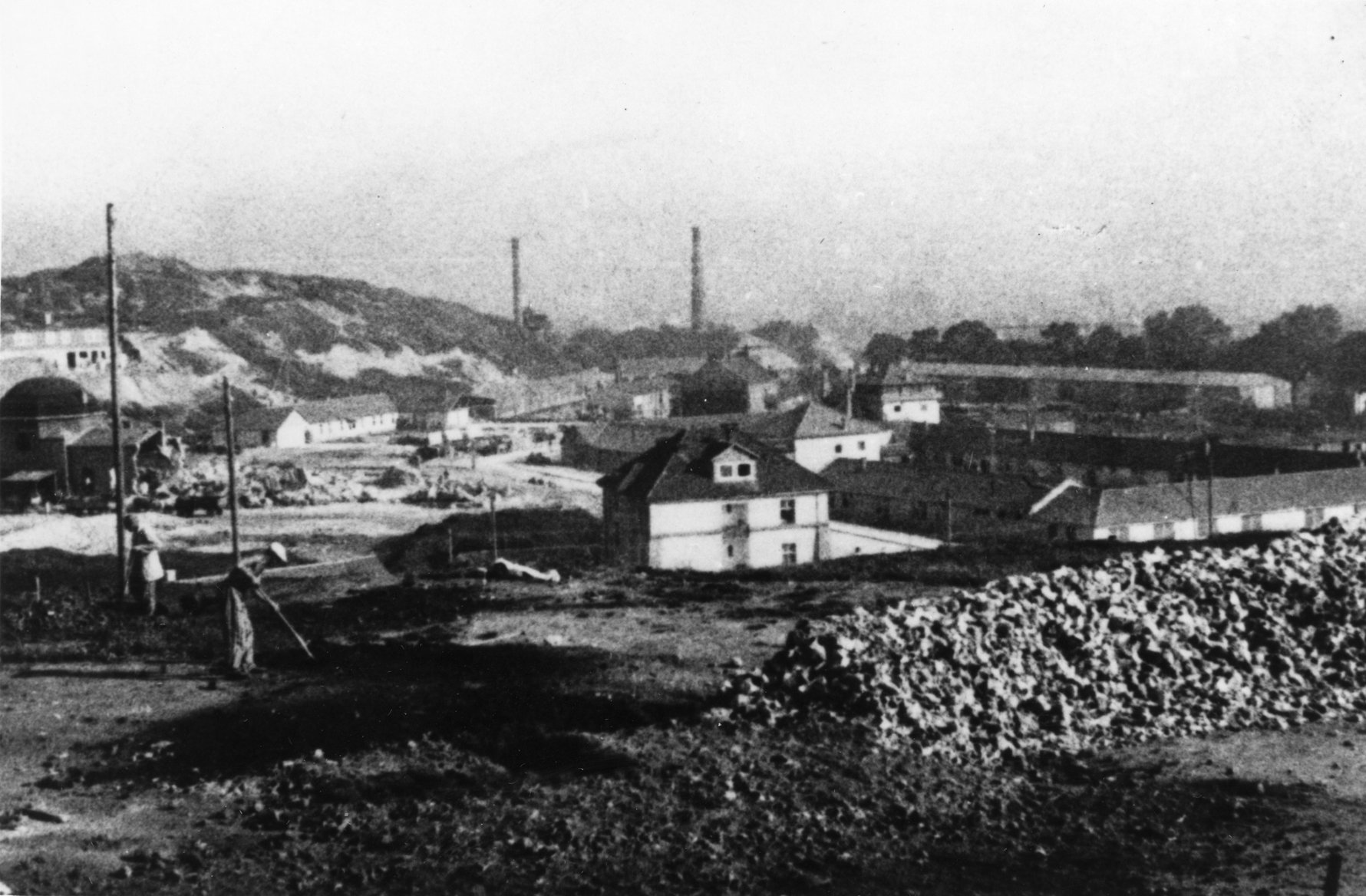

At the same time, the building of the Płaszów camp (which would precipitate the ghetto’s liquidation) was underway on the other side of the Krzemionki hills which overlooked the Ghetto. Only four kilometres from Kraków’s market square, the site was chosen for its proximity to a handy railroad station, an existing labour camp in the nearby Liban quarry, and its convenient location on top of two Jewish cemeteries – both of which were levelled, with the shattered tombstones used to cobble the lanes of the camp and whole tombstones used as pavers to create the main road. This was standard Nazi practise for humiliating and terrorising their victims.

First established as a forced labour camp in the summer of 1942, Płaszów soon became a favoured execution site for the Nazis as cattle cars full of children, the elderly and infirm were sent from the ghetto only to be systematically murdered and fill mass graves at the camp. Built with the sweat of slave labour, from autumn 1942 all those deemed ‘fit to work’ commuted every day from the Ghetto to participate in the construction of their future prison, and from January 1943 many no longer returned to the Ghetto, but stayed in the unfinished camp barracks. When Amon Goeth took over as KL Płaszów Camp Commandant he wasted little time, speeding construction of the camp and liquidating the Kraków Ghetto only a month later. On March 13th and 14th, 1943, some 6,000 Jews were permanently transported from the Kraków Ghetto in Podgórze to Płaszów; 3,000 were sent by cattle car directly to the gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau, and some 1,000-2,000 (accounts vary) others were shot in the street, their bodies later transported to Płaszów and buried in mass graves.

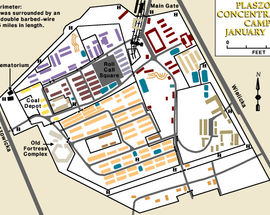

After Goeth’s arrival, Płaszów developed rapidly, becoming a destination for many Jews and political prisoners from southern Poland and beyond. Conditions were abysmal; following the liquidation of the Kraków Ghetto the average barracks contained 150 inmates in a space of about 80 metres, and by the summer of 1943 the number of inmates had ballooned to over 12,000. At its height in 1944 it is estimated that there were 25,000 prisoners interred within the camp, which covered some 81 hectares (200 acres) surrounded by four kilometres of electrified barbed wire, and guarded by twelve watchtowers equipped with machine guns and spotlights.

As the camp expanded, separate living quarters were established for the men and women, Poles and Jews, as well as an administrative sector for the SS officers. The camp also included a large assembly square, hospital, mess hall, isolation cells, stables, bathhouse, bakery and the various workshops where inmates worked extremely long hours without rest or enough food to stave off starvation. In addition to the many on-site workshops, inmates also provided free labour to several local factories, Oskar Schindler’s enamelware factory in Zabłocie among them.

Slave labour or not, having such a job (which provided a small amount of security to many Jews who were quite skilled) was certainly preferable to not having one, and immensely better than working in one of the two limestone quarries located at Płaszów, which was essentially a death sentence; the average life expectancy for quarry workers was a mere matter of weeks. Prisoners also faced death from disease (typhus and malaria were rampant in the camp), starvation, and the cruelty of their captors. The Płaszów camp and its staff, led by Amon Goeth - who took pleasure in arbitrarily murdering the inmates, made themselves famous for their sadistic treatment of the camp’s prisoners. Personal accounts from Płaszów portray Goeth as a mass murderer instructing his staff to make sport out of the suffering and execution of the inmates.

From January 1944, Płaszów was officially designated as an independent concentration camp with satellite camps in Wieliczka and Mielec. Jews from smaller camps and ghettos that were being liquidated across Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Romania were sent to Płaszów, however many of them never made it inside the camp. Covered transport trucks full of Jews arrived several times a week and were taken directly to one of two mass execution sites where the condemned were shot, thrown into a mass grave and covered in dirt and lime, layer upon layer. Plans to install a crematorium at the camp were drawn up but never carried out, with the efficiency of Auschwitz-Birkenau in this regard – to which many transports from Płaszów were sent – likely being a factor.

Calculating the number of people who lost their lives at the camp is impossible; a rough estimate of the number of prisoners interred here over its less-than-two-year history would be in the neighbourhood of 150,000, but Nazi records fail to give us anything more than a speculative guess. Liquidation of the camp began in early January 1945, with the last prisoners leaving on death marches to Auschwitz; those who reached it were killed in the gas chambers immediately upon arrival. As the Soviet Army approached Kraków the camp was completely dismantled, and the Germans exhumed the primary mass graves, burned the bodies and spread the ashes all over the site in an effort to hide their crimes. What the Soviets saw upon arrival in 1945 doesn’t differ that much from what you see when visiting today - a barren field.

Approximately 2,000 Jews and Gentiles who passed through Płaszów are known to have survived the war; 1,000 of these were the ‘Schindler Jews’ who escaped from Kraków to Brunnlitz before the war’s end.

VISITING KL PŁASZÓW TODAY

Getting to Płaszów

Due to its size and the fact that there is no prescribed route, there are several ways to get to the territory of the former Płaszów camp. If you have a car you can drive around to the southern side of the camp and park on the side of the road across from Castorama on ul. Henryka Kamieńskiego within view of the ‘Memorial of Torn-Out Hearts.’ It is also possible to park on the eastern side by driving south down ul. Wielicka, turning right onto ul. Abrahama and parking near the ‘Grey House.’

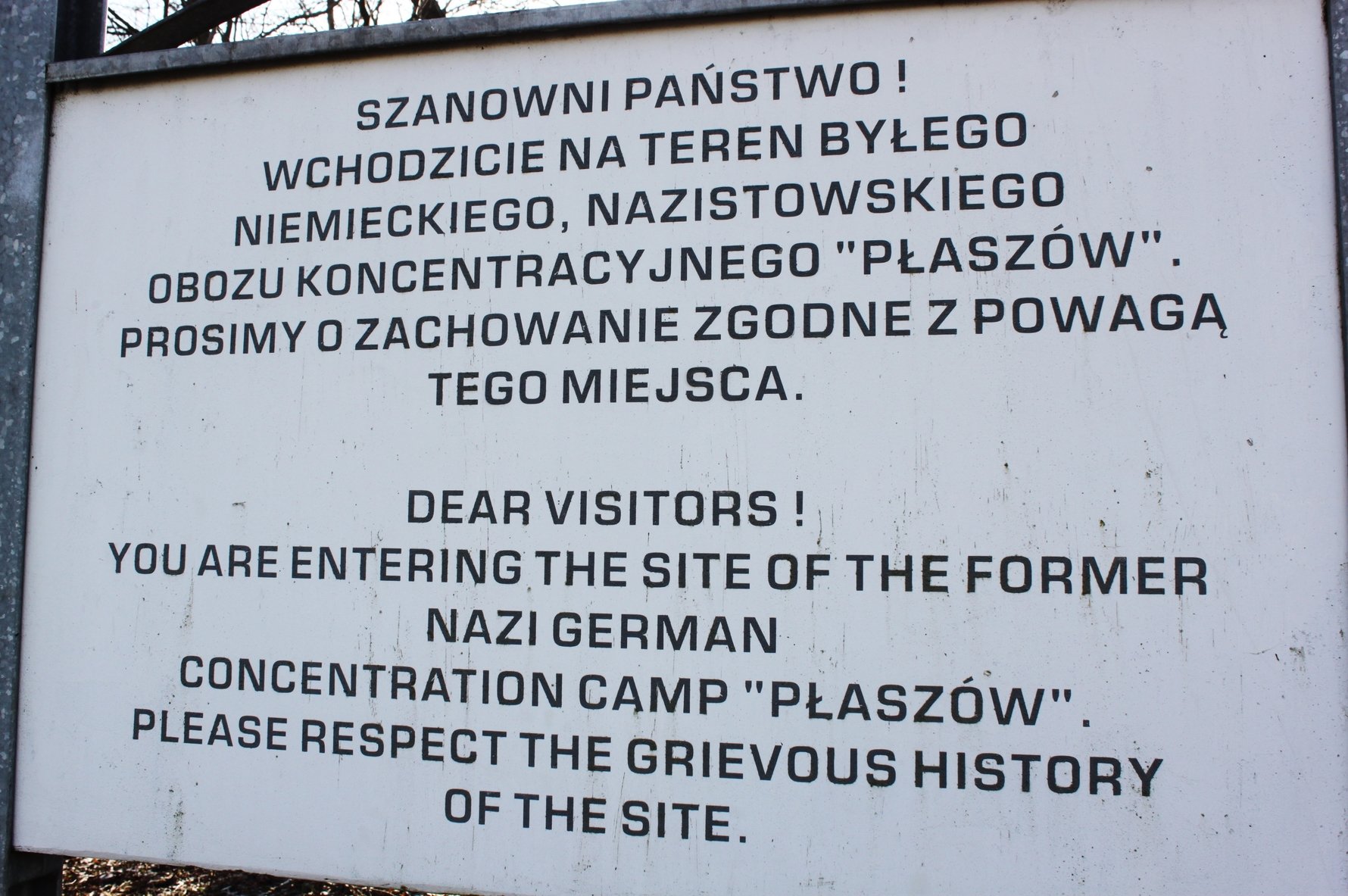

Without a car, the most straight-forward approach is to take a tram to the 'Cmentarz Podgórski' stop (use krakow.jakdojade.pl for connections). After getting off the tram walk south (away from the centre) down ul. Wielicka (the main road) and after 300 metres(/3mins) make a right onto ul. Jerozolimska. 100 metres later you will have arrived at what was once one of the main entrance gates to the camp, located just before the former Guardhouse; a sign on the right side of the road let's you know you have arrived at the area of the camp.

A more scenic, adventurous and time-consuming (but worthwhile!) alternative is to get off the same tram a stop earlier at ‘Podgórze SKA’ and access the camp via a trail leading away from Krakus Mound. To get to the mound cross over Al. Powstańców Wielopolskich and go through the overpass tunnel, making a right onto ul. Robotnicza; Robotnicza leads you uphill and to the right to a paved footpath that crosses over Al. Pod Kopcem and carries you uphill towards the Mound (20mins), which offers great panoramic views over Kraków. A trail behind the Mound then leads you to a narrow path between the edge of the New Podgórze Cemetery and the rim of Liban Quarry; follow the rim of the quarry until you get to some abandoned buildings (this is clearly the most intriguing route) and make a left, walking away from the quarry until you reach the camp from the west (10mins). There is a sign in the area that tells you when you entering the former camp.

What To See

Today almost nothing remains of the sprawling 80-hectare concentration camp in Płaszów – a district of Podgórze. In comparison to other Nazi prison camps, Płaszów was extremely well dismantled and has been the subject of very little historical excavation or on-site documentation until only recently (in summer 2017 archaeological works were undertaken in several parts of the camp). Those private homes which were commandeered by the Nazis and incorporated into KL Płaszów were returned to their owners after the war and today sit on the fringes of the former camp as inauspiciously as any other homes in the area. Large apartment blocks have been built on top of other parts of the former camp. As a result it is very difficult to grasp the scope of the camp or imagine what it looked like during the war, though an outdoor exhibit of 19 archival photographs with brief historical information now offer visitors some clues about the camp’s layout. Installed in November 2017, these sparse photo plaques are the first and currently the only exhibits on the territory of the camp, however the site is currently being developed to host a proper museum, slated for a 2025 opening.

With the exception of the new photo plaques, visitors are mostly left to their own imaginations and private thoughts while walking through the grounds, keeping their eyes peeled for traces of the past. Several memorials, monuments and points of interest do exist, however, and we list them below. We encourage visitors to make the walk from the north side of the camp to 'C Dołek' and the large, easily visible monument to its victims on the southern side, taking in as many of these sites as possible en route. As you do, of course, bear in mind that though the area looks like little more than a neglected public park, this is actually a sacred place of remembrance. In addition to whatever remains exist from the two Jewish cemeteries once located on this site, it is speculated that the remains of 8,000-10,000 Płaszów prisoners are still located within the area of the camp. As a few signs near the edges of the camp clearly state: “Please respect the grievous history of this site.”

Use the map below and the list of connected venues at the end of this article in exact order to explore the KL Płaszów Concentration Camp from north to south, or read on for an abbreviated description of both sides of the camp and what you'll see there.

The North End of the Camp

If you approach the camp from ul. Jerozolimska in the north, you have the greatest chance of seeing the most points of interest. This was also the main entrance into the camp. At the corner of ul. Jerozolimska and ul. Abrahama (which turns from a paved road between the apartments blocks into a dirt trail leading into the camp) you can consider that you are now inside the former camp, and a sign across the road tells you as much. On this corner at ul. Jerozolimska 3 stands the infamous ‘Grey House,’ used as a prison and torture chamber by the SS during the camp’s existence.

Turning right onto ul. Abrahama, which once ran through the middle of the camp, you’ll find a small monument only about 20 metres from the Grey House. Though not directly related to the camp (which was yet to be built), this memorial remembers the site where 13 Poles were murdered by the Nazis on September 10th, 1939 – the first mass execution of WWII in Kraków. Across the path to the left you should be able to see the camp’s limestone deposits and even find the entrances to three anti-aircraft shelters carved into the rock by prisoners.

A paved path to the right leads to another monument close behind Grey House, this one also not related to the camp (notice the trend), but to the Jewish Cemetery that formerly stood here. This new tombstone marks the burial place of Sara Schenirer, founder of the Beth Jacob School – the first religious school for girls in Kraków (1917, ul. Stanisława 10), which became a model for Jewish schools all over Poland in her time (over 300 before she died in 1935), and for many schools in Israel, the US and elsewhere today.

Following the worn footpath straight back from here (away from ul. Abrahama), about 25 metres away is a grove of trees where close inspection reveals extensive piles of concrete rubble that were once the Podgórze Jewish Cemetery’s magnificent pre-burial hall. Built in 1932, part of the hall was detonated by Goeth to amuse his company one night, while the rest was dismantled at the end of the war.

Head left/due west from the funeral parlour ruins and you should be able to pick up a trail heading north (to your right) that will lead you directly to the only other visible evidence of the forgotten Jewish cemeteries in Płaszów (about 30 metres). Conservation works have recently exposed scores of graves which were formerly completely overgrown and obscured by brush. Chaim Jakub Abrahamer, laid to rest in 1932, has the distinction of the only legible surviving headstone, surrounded by the anonymous foundations of other graves.

The South End of the Camp

From the intersection where the Grey House stands, cross ul. Abrahama and continue up ul. Heltmana (the continuation of ul. Jerozolimska). This residential street was known as ‘SS-strasse’ during the war for it was here that the Nazi officers lived, including camp commandant Amon Goeth at number 22, known as the ‘Red House.’ You can see the back of the house by making a detour onto ul. Lecha, and if you follow it to the end and make a left onto the dirt trail there it will lead you to 'H Górka'. One of the camp’s mass execution sites, it was here that the Nazis later exhumed the bodies of 10,000 Jews and burned them to hide their crimes. The name is a vulgar bit of Polish word play taken from the name of the SS officer who ordered the first executions here (Albert Hujar) and the Polish word for the male member; a print-friendly translation would be ‘Prick’s Hill.’ Today the site is marked by a modest wooden cross with a crown of thorns.

From here you can see the large stone monument, which stands atop 'C Dołek' - Płaszów’s other main execution yard. Towering over not only the camp, but also the highway towards which it unfortunately faces, this monolithic Soviet-era monument is known as the ‘Memorial of Torn-Out Hearts.’ Designed by Witold Cęckiewicz and unveiled in 1964, the inscription reads, “To the memory of the martyrs murdered by the Nazi perpetrators of genocide in the years 1943-45.” Near its base are two other monuments: to the left, a low-lying plaque remembering the Hungarian Jewish women processed in Płaszów on their way to Auschwitz; to the right, a stone obelisk commemorating all the Jewish victims of the camp. The last line of the long text reads, “In memory of those murdered, whose final scream of anguish is the silence of this Płaszów graveyard.”

Comments