Wrocław, believe it or not, had a total of eleven (eleven!) native-born Nobel laureates in the 20th century, beginning with Thomas Mommsen’s prize for literature in 1902 and spanning Richard Selten’s 1992 prize for his work in game theory. While all of Wrocław's Nobel nerds are arguably worthy of in-depth investigation, perhaps none of their stories are as sensational, complex and significant as that of German chemist Fritz Haber (1868-1934), one of the most important scientists in human history.

Early Life & Career

during her studies at University of Breslau.

Passing his high school exams in Breslau/Wrocław, Fritz began an apprenticeship at his father's company, swiftly became intrigued by the consequences of combining various chemicals, and soon left to study chemistry in Berlin, then Heidelberg, then back to Berlin, where he earned his PhD. Using his father's connections, he flitted between apprenticeships and the family business, but clashed too often with his father to sustain the latter, eventually taking teaching positions at the University of Jena (where it should be noted he converted to Protestantism) and finally a full professorship at the University of Karlsruhe. It was in Karlsruhe that Haber's name began to receive recognition, and then renown, as he collaborated with other top German minds and authored several books based on his research of dyes and textiles, electrochemistry, chemical thermodynamics, free radicals and other concepts we won't feign to comprehend.

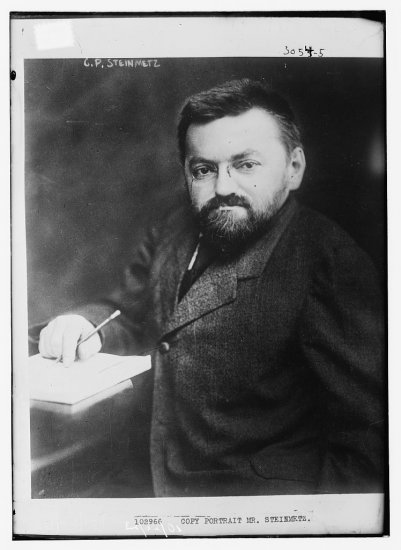

Although shunned by his father, Haber found a companion in fellow genius, chemist and Breslauer, Clara Immerwahr - a brilliant scientist in her own right, and the first woman in Germany to earn a doctorate degree (in Chemistry, from the University of Breslau). A strong pacifist and women's rights advocate, Immerwahr refused Haber's marriage proposals in favour of her own independence, career and research for over a decade before finally marrying him in 1901 at age 31. A year later, their only child, Hermann, was born.

Birdshit Crazy Science: Ending the 'Guano Age'

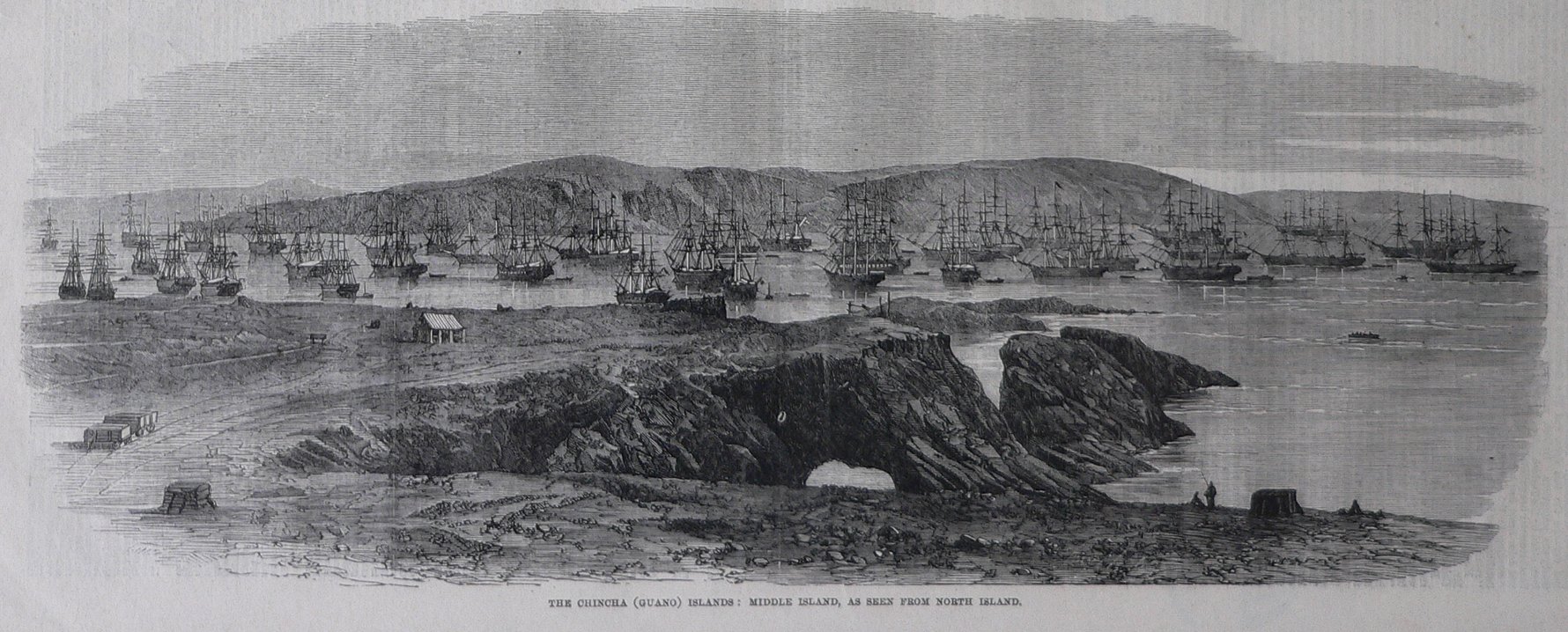

All the while, the world had a problem. Its natural resource for ammonia and nitrogenous compounds – necessary to the production of fertilisers and thereby food – was not large enough to meet rising global population numbers and increasing worldwide demand. In 1802, Prussian explorer Alexander von Humboldt had discovered these coveted properties in massive guano deposits - that is, enormous piles of bird excrement - off the western coast of South America and sparked the 'Guano Age': 100 years of mining, harvesting, pirating and imperialism all centred around the world's bird and bat poo supply. From 1865-1883, multiple full-fledged wars (dubbed names like the 'Guano War,' 'Saltpetre War' or 'Nitrate War') were even fought between Spain, Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador and Chile over their claims to coastal guano deposits. If you're not sure who eventually came out on top in those conflicts, just look at a map of South America (it was Chile). We shit you not, much of 19th-century economics, exploration, colonialism, imperialism and island landgrabbing (including much by the United States) was all predicated by a desire to acquire massive quantities of nitrate-rich bird droppings (kinda like oil in the 20th century).

The world's demand for guano was not at all sustainable, however, and by the early-20th century, the world's precious supply of easily-mined guano lay almost exclusively in one last 355 kilometre-long, one-and-a-half metre-deep deposit off the coast of what was now Chile (to the victor go the spoils). With the Chileans holding a monopoly over the world’s ability to produce ammonia thanks to their unique ‘deposit,’ they basically had the world over a barrel and could set whatever prices they wanted. With the entire problem boiling down to the natural nitrates in the waste itself, in stepped Haber the uber-chemist. Abandoning an initial project to develop an addictive laxative for the common German house sparrow (–this is the only part we made up), Haber invented a process for producing ammonia in his lab from abundantly available nitrogen and hydrogen gas in 1911. In doing so, he accomplished a milestone in industrial chemistry and also forever changed the world economy and agriculture. Teaming with Carl Bosch at BASF, Haber and Bosch successfully scaled up the process to industrial levels and for all intents and purposes saved the world from the impending food crisis many were predicting, as suddenly inexpensive fertilisers could be made all over the globe. As a consequence they also torpedoed the Chilean economy, as the birdpoo market bottomed out, never to recover.