It’s hard to go anywhere in Poland without being reminded of one of the darkest chapters in the history of humanity, and Kraków, for all of its beautiful and intoxicating diversions, really shouldn’t be any different. While thousands of tourists use Kraków as a jumping-off point for visiting Auschwitz, few seem to realise that Kraków actually has a former concentration camp in its own backyard.

While plans to build a museum here are now finally underway, as of right now (spring 2024) the only exhibits consist of outdoor informational plaques at certain points around the park. In contrast to Auschwitz, there are no professional tour guides here, no headsets, no multimedia displays, no instructions or design for how to experience the space (except those in this guide). In that sense Płaszów is more of a pilgrimage than a destination, and offers to those who walk its obscure paths the opportunity to engage the past without any pressure or pretence. This is a place where the lives of thousands of people came to an end; a mass cemetery of unmarked graves; the most horrific place in Kraków; and also the most peaceful.

History

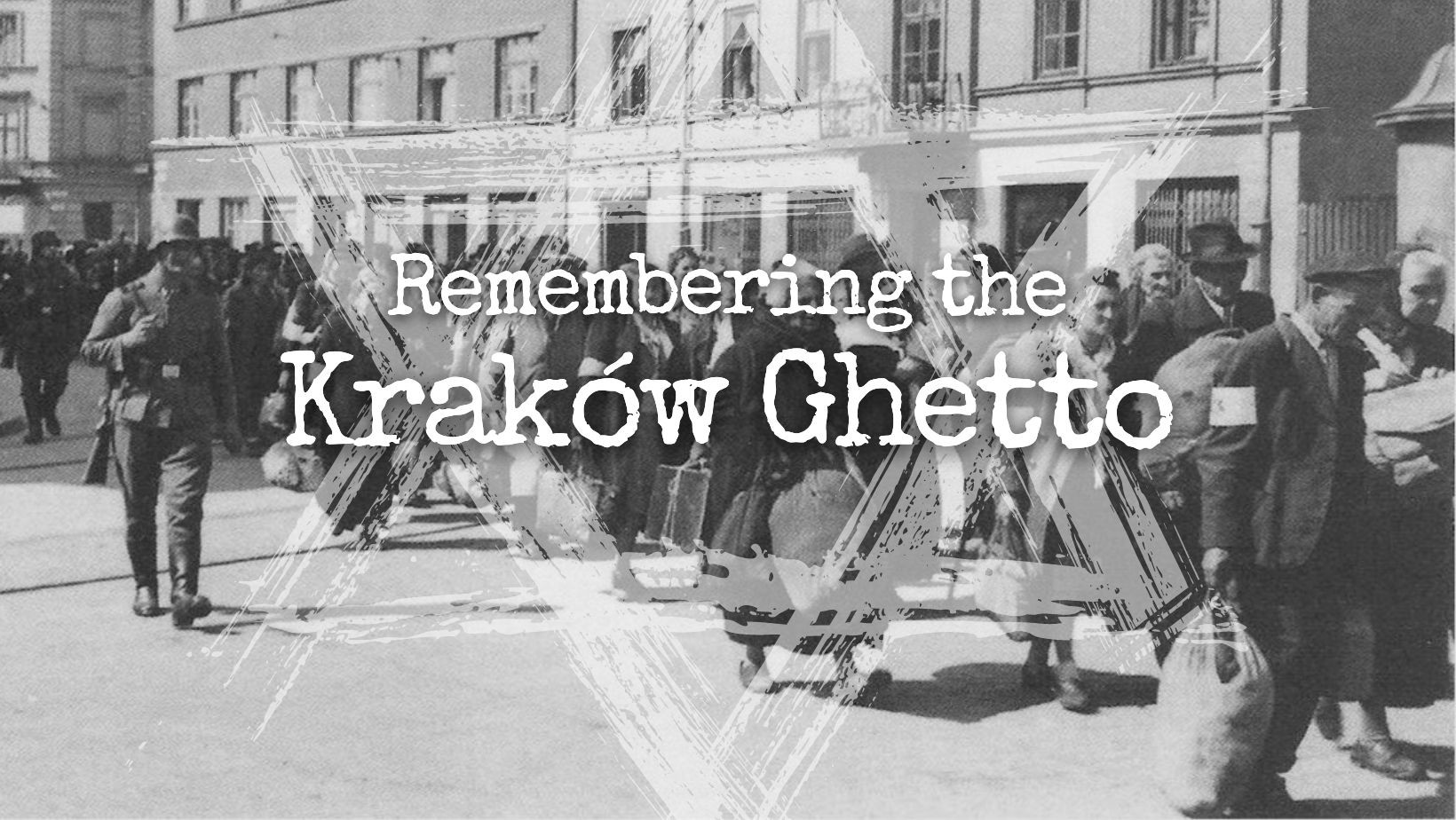

Before World War II, Kraków was home to some 65,000 Jews, who once under Nazi occupation (beginning in September 1939) faced almost immediate persecution. Forced ‘resettlement’ (largely to labour camps in the east) began in late 1940 and by the time of the establishment of the Kraków Ghetto in March 1941, the Jewish population had been reduced to some 16,000 individuals crammed into a 20 hectare (50 acre) space in Podgórze. In early 1942 the Nazis began to initiate Hitler’s ‘Final Solution,’ ramping up terror in the Kraków Ghetto with increased round-ups, deportations and street executions that resulted in the gradual reduction of the size and population of the ghetto.

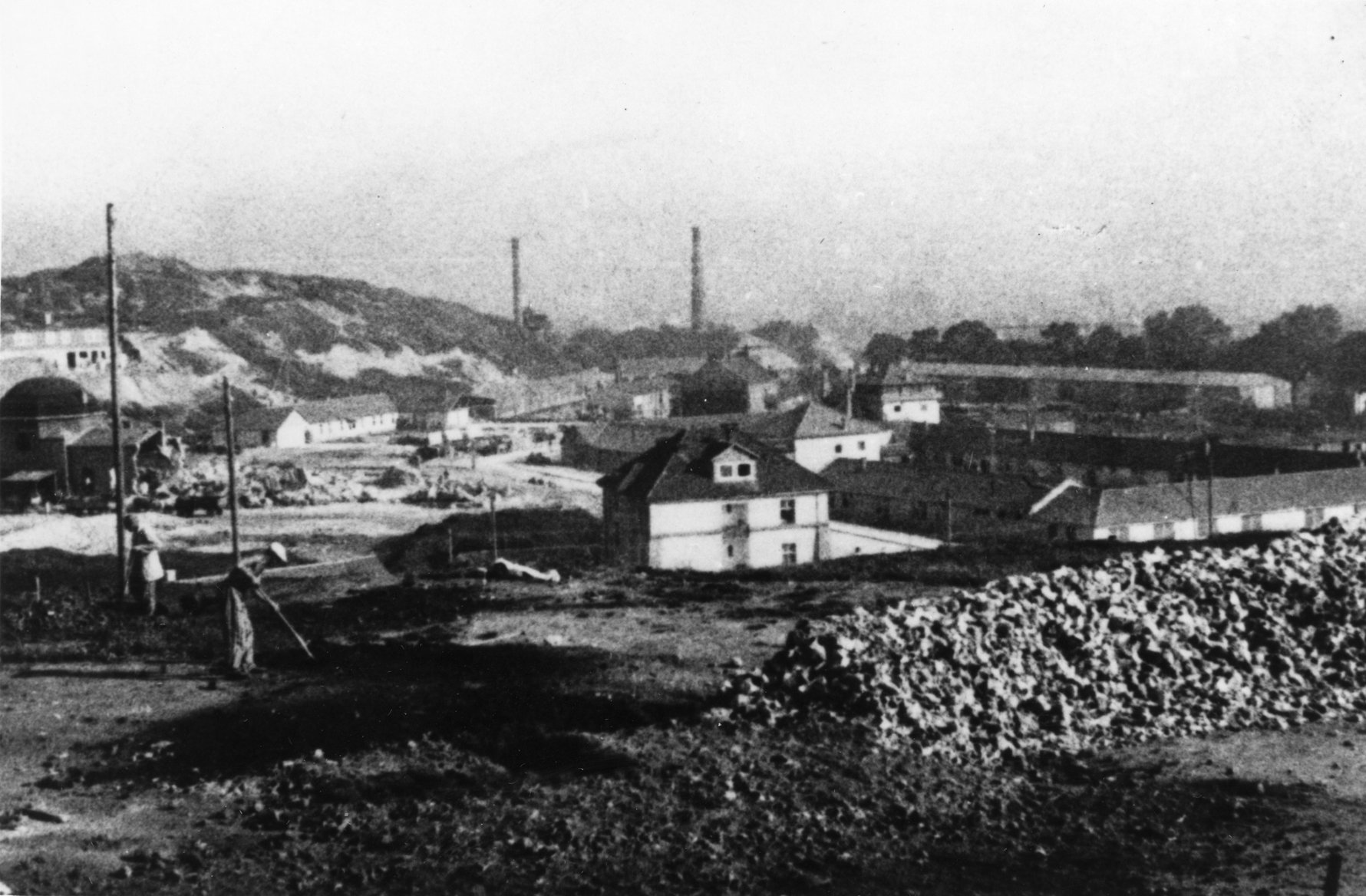

At the same time, the building of the Płaszów camp (which would precipitate the ghetto’s liquidation) was underway on the other side of the Krzemionki hills which overlooked the Ghetto. Only four kilometres from Kraków’s market square, the site was chosen for its proximity to a handy railroad station, an existing labour camp in the nearby Liban quarry, and its convenient location on top of two Jewish cemeteries – both of which were levelled, with the shattered tombstones used to cobble the lanes of the camp and whole tombstones used as pavers to create the main road. This was standard Nazi practise for humiliating and terrorising their victims.

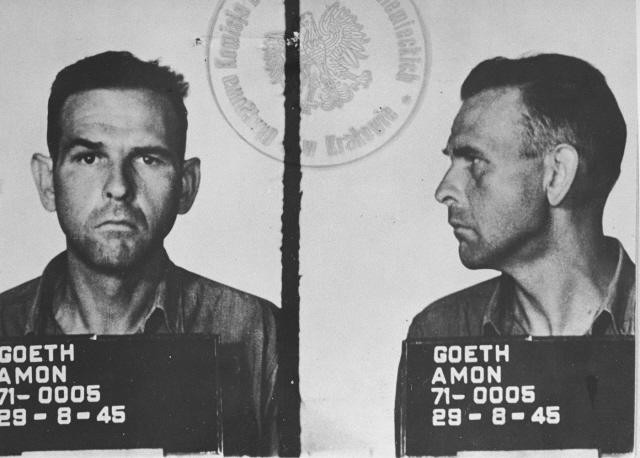

First established as a forced labour camp in the summer of 1942, Płaszów soon became a favoured execution site for the Nazis as cattle cars full of children, the elderly and infirm were sent from the ghetto only to be systematically murdered and fill mass graves at the camp. Built with the sweat of slave labour, from autumn 1942 all those deemed ‘fit to work’ commuted every day from the Ghetto to participate in the construction of their future prison, and from January 1943 many no longer returned to the Ghetto, but stayed in the unfinished camp barracks. When Amon Goeth took over as KL Płaszów Camp Commandant he wasted little time, speeding construction of the camp and liquidating the Kraków Ghetto only a month later. On March 13th and 14th, 1943, some 6,000 Jews were permanently transported from the Kraków Ghetto in Podgórze to Płaszów; 3,000 were sent by cattle car directly to the gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau, and some 1,000-2,000 (accounts vary) others were shot in the street, their bodies later transported to Płaszów and buried in mass graves.

After Goeth’s arrival, Płaszów developed rapidly, becoming a destination for many Jews and political prisoners from southern Poland and beyond. Conditions were abysmal; following the liquidation of the Kraków Ghetto the average barracks contained 150 inmates in a space of about 80 metres, and by the summer of 1943 the number of inmates had ballooned to over 12,000. At its height in 1944 it is estimated that there were 25,000 prisoners interred within the camp, which covered some 81 hectares (200 acres) surrounded by four kilometres of electrified barbed wire, and guarded by twelve watchtowers equipped with machine guns and spotlights.

As the camp expanded, separate living quarters were established for the men and women, Poles and Jews, as well as an administrative sector for the SS officers. The camp also included a large assembly square, hospital, mess hall, isolation cells, stables, bathhouse, bakery and the various workshops where inmates worked extremely long hours without rest or enough food to stave off starvation. In addition to the many on-site workshops, inmates also provided free labour to several local factories, Oskar Schindler’s enamelware factory in Zabłocie among them.

Slave labour or not, having such a job (which provided a small amount of security to many Jews who were quite skilled) was certainly preferable to not having one, and immensely better than working in one of the two limestone quarries located at Płaszów, which was essentially a death sentence; the average life expectancy for quarry workers was a mere matter of weeks. Prisoners also faced death from disease (typhus and malaria were rampant in the camp), starvation, and the cruelty of their captors. The Płaszów camp and its staff, led by Amon Goeth - who took pleasure in arbitrarily murdering the inmates, made themselves famous for their sadistic treatment of the camp’s prisoners. Personal accounts from Płaszów portray Goeth as a mass murderer instructing his staff to make sport out of the suffering and execution of the inmates.